Black in Kidlit Thursday.

I’ll just come out and say it.

Children’s literature criticism is antiblack as hell.

Things were bad before the pandemic, but manageable. I’d found ways. “That’s just how they are.”

Things were bad before the pandemic, but manageable. I’d found ways. “It’s a very White field.”

Things were bad before the pandemic, but manageable. I’d found ways. “Diversity isn’t just Black and White.”

Antiblackness.

Bad before the pandemic.

Unbearable now.

I can’t believe everything I've witnessed and experienced since mid-March in the children’s literature world…

Wait.

Yes, I can.

I’ve been here for a long time.

*

In a pandemic, with Black lives in the crucible, there is no mercy for Black folk. Not much respite. Very little rest.

There is no space for our Black selves to be human. To have limits. To need things.

Even when we bend over backwards to support, celebrate, elevate, and reciprocate, more is demanded.

It’s not enough.

Even when we take public hits.

Even when we give what should have never been asked.

Even when we are expected to mediate.

Even when we are expected to understand.

There is no space for Black people in children’s literature criticism.

There is a constant negation of Black people who aren’t Magical or Famous or Safe or Serving You In Some Way in this field.

Black scholars before my time have been driven out, marginalized, memories of their work suppressed.

Younger and newer Black scholars are still being driven out, marginalized, the promise of their work nipped in the bud.

(We won’t even get into what Black women authors and illustrators have gone through in the industry… that’s another tale for another time.)

There is an often tacit, sometimes overt, expectation of endless gratitude, groveling, and stroking to assure that everyone concerned are Good People Who Mean Well.

Oh, my God. Lord, have mercy…

They’ve got one more time.

My therapist asked me about a month ago after I was “called out” by someone I’d considered a mentor, introduced to my friends, centered in my work, and continually stroked and catered to in numerous ways… only to be treated as a wayward, bigoted child, not as a colleague…

“What wound has been picked at by this interaction?”

Recently, I have been taking inventory of my recent interactions with people in children’s literature.

How did you end up here, Ebony?

How did you end up dealing with people who have known you for most of your adult life, and don’t give a single solitary damn that you’re exhausted, and need a breather from being Their Black Person?

How did you end up dealing with people who have known you for most of your adult life, and refuse to listen to you?

What happened?

I think I know.

*

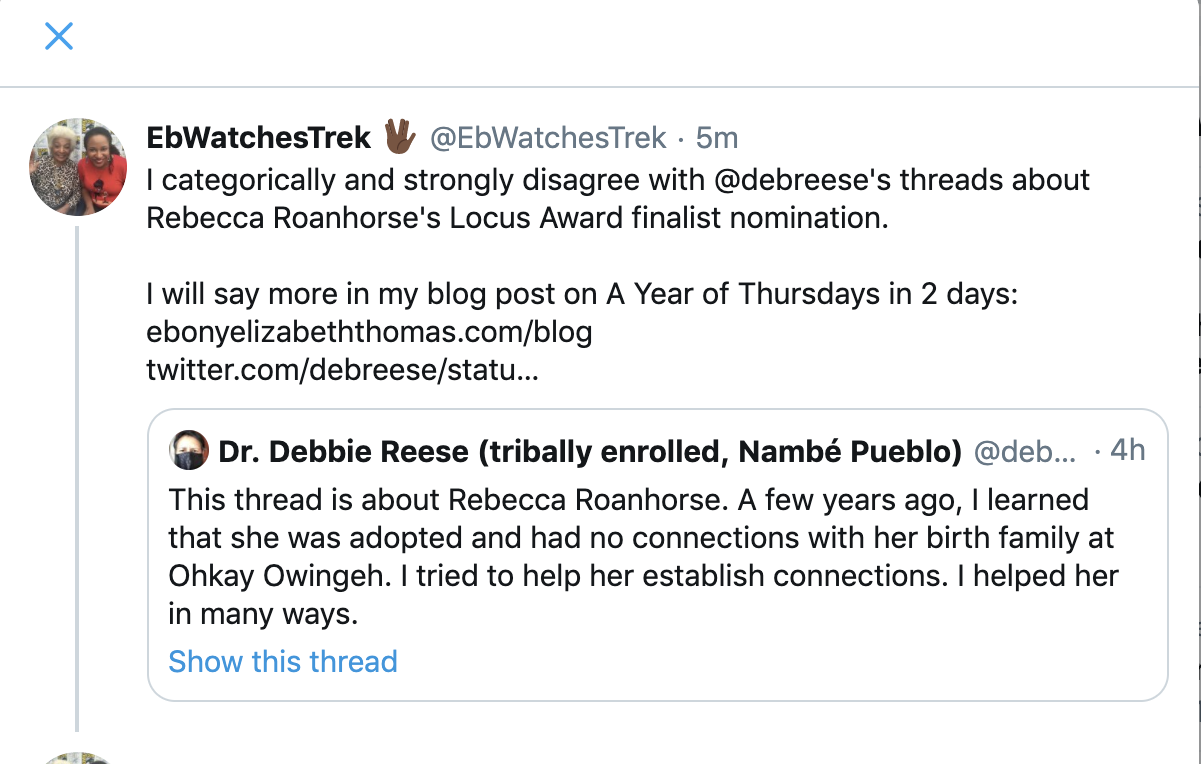

On Tuesday afternoon, while I was on the phone with my mother, several Black authors, as well as other stakeholders in children’s and YA literature were responding to a thread about Hugo, Nebula, and Locus award winning speculative fiction author Rebecca Roanhorse by a colleague and mentor whom I considered to be a close friend, Dr. Debbie Reese of American Indians in Children’s Literature.

It was a thread in response to the announcement that Rebecca’s book, Storm of Locusts, was a finalist for the 2020 Locus Award. Debbie mentioned her previous critiques of Rebecca’s work and her dismay about the announcement.

However, she also engaged in a personal attack about her background that had absolutely nothing to do with the issue at hand.

I did not see the Tweets until I was alerted by Debbie herself. After I learned what was going on, I was horrified. I agreed with Patrice Caldwell’s take.

I want to be respectful of people’s right to critique their culture.

That’s always been my stance when it comes to Native children’s and young adult literature: Talk to Debbie.

Before Tuesday, I’d always deferred to Debbie when it came to Native and Indigenous issues in children’s literature. She is tribally enrolled at Nambe Pueblo. She has been doing this work for more than 3 decades. She has earned a PhD and an MLIS. She is an #ownvoices critic who has won multiple awards for her work.

If Debbie said a book in her lane had problematic Native content, to me, it did. Period. So while I loved “Welcome To Your Authentic Indian Experience,” followed Rebecca on Twitter, and cheered loudly when she won her initial awards, once Debbie talked to me, and I read her reviews, I stopped boosting and RTing her stories.

I always deferred to Debbie when it came to Native and Indigenous issues in children’s literature.

I wanted to support my friend, as she’d supported me.

(More about that later.)

This is a really hard time for Black people. So many of us are exhausted and depressed. Let us not give a Black woman any more to deal with by dragging her work today.

I was on the phone with my mother when all this began. Everything is on fire right now and I am The One Who Everyone Is Leaning On across a few different circles.

I tried my best to multitask, all while explaining to my mom why this random children’s lit thing meant I had to hang up… on my mom, who didn’t get it.

Then I started getting texts.

Again, I tried to multitask. (Keep in mind that I’m also doing an asynchronous summer school course and was chatting with students.) I didn’t check Twitter right away. I am taking the summer off from my @Ebonyteach Twitter account, and didn’t go look.

Before I actually read the threads, I was still thinking of ways for my friend to dial things back. I was trying to problem solve. I was thinking of her.

Then I heard from a Black author friend of mine. One who never gets involved in these social media controversies.

We talked for a good while.

She gave me 4 things to ask that she and other Black authors were wondering about the situation. Things to consider.

Not attacks. Reasonable points.

I sent them along to Debbie.

We had a brief exchange.

My mom called again. I was in the middle of everything. I said I’d call her back.

I told Debbie I needed 24 hours away. Family > children’s literature. Always.

Then I heard from a Black professor friend who works in an adjacent field. She was absolutely furious.

“You have to say something, right now, or you’ll damage all your credibility. What she wrote was antiblack as hell.”

She wasn’t wrong. Children’s literature criticism is antiblack as hell, I reflected.

When I read the threads, stopped everything else I was doing, and understood, I was very upset.

I quickly fired off 2 Tweets from my Trek fan account, tearing a huge rift in one of my longest professional friendships.

“I categorically and strongly disagree with Debbie Reese’s threads about Rebecca Roanhorse’s Locus Award nomination. I will say more in my blog post on A Year of Thursdays in 2 days.”

“I’m off @Ebonyteach for the summer, but I want to be clear about my uncompromising support for BW writers. I apologize for my past misplaced loyalties in @debreese’s conflicts with authors. I was wrong.”

This is that post.

But this post isn’t (just) about Debbie.

It is about the way that Black people working in children’s literature are routinely treated.

*

Context is everything.

My literary and academic reconnections to my child and teen selves, and to Black feminism, have been recent.

My Blackness was never something that needed an awakening within mainstream institutions. It was never in question.

I’m Detroit Black. HBCU Black. Up South, Westside, Great Migration Black.

I’m devastating Delta diva Black. Baptist church choir-altar-girl-and-Sunday-School Black. Cook my ass off, house stays on point, Mama-and-Grandma’s eldest girl Black.

I am Black on every side, each and every which way, Black.

In the beginning, Blackness was all I knew.

But the Black world that I came of age in was besieged on all sides. I understand that now, although 20 years ago, I resented it and wanted escape…

No.

It wasn’t escape from Blackness that I wanted.

It was escape from Black pain.

By the time I was in my 20s, I wanted respite.

Respite came when I rediscovered children’s literature as a 22 year old fifth grade teacher. Multiple cascading personal tragedies led to falling straight down the rabbit hole of the Harry Potter series in February 2000. More than 20 years ago.

It wasn’t respite from Blackness that I wanted. I love being Black.

It was respite from the pain.

I wanted to be Black without the pain.

And you know, I thought I had all figured it out…

I thought I could be Black with a minimum of pain in children’s literature. In 2000, in early Harry Potter fandom, I could believe, or at least pretend, that the racial Singularity was nigh, as adults (and later, we learned, some teens) from all over the world came together to talk about a story and characters and a world we’d all fallen in love with.

I fell straight up in love with Potter’s wizarding world. That love replaced the man who didn’t want to be with me. It assuaged the wounds from my father’s death. It gave me a diverse group of friends from every background.

That love led me to Nimbus – 2003. It was there that I met a couple of professors – Karin Westman and Philip Nel — who complimented me on my presentation and invited me to stay in touch.

I joined the Rutgers Child_Lit listserv.

I was 25 years old. Almost 26.

It was the early summer of 2003. 17 years ago.

I’ve told part of this story before, in The Dark Fantastic.

But I did not share what happened next. I shared only the fandom controversies.

I didn’t talk about how I became a children’s literature critic.

*

I was a member of Rutgers’ Child_Lit listserv from 2003 until it ended, with archives deleted, in 2017, if I recall correctly.

After 2014, I posted less and less on the list. I was on the tenure track. I’d discovered that Black feminist Twitter was a place where I could exhale. And the conversations happening about children’s lit over there were refreshing.

The last time I felt as dismal as I do now about being Black in children’s literature criticism was during the polar vortex in February 2014, during a month of conversations about diversity.

Walter Dean Myers and Christopher Myers wrote their twin New York Times essays the next month. By the end of spring, We Need Diverse Books was founded.

The backstory of the entire social media age diversity in kidlit movement is in those missing archives. Most engaging in the conversation since then don’t know the full backstory.

The missing backstory is (in part) in that (deleted) February 2014 conversation.

Context is everything.

You can delete decades of conversations.

You can’t delete people’s memories.

*

I had been a member of Child_Lit for 12 years before someone mentioned the extraordinary Council on Interracial Books for Children directly to me.

That person was not in children’s literature.

It was Dr. James Banks, the preeminent Black scholar of multicultural education. I have seen many people mentioning Robin DiAngelo’s work; Dr. Banks mentored her, and many others.

Dr. Banks was the first who asked me if I had ever heard about the CIBC.

We were at the National Academy of Education / Spencer Fellows retreat in Washington, DC. The second of three.

I was in my fifth year as a tenure track professor.

I had been a member of Child_Lit for 12 years.

Context is everything.

*

Context is everything.

I was at my third and final National Academy of Education / Spencer Fellows retreat when the first of two #SlaveryWithASmile picturebook controversies arose.

A flame that had been lit the spring and summer before burned hot by the fall of 2015. In the year and a half since that frigid February 2014 on Child_Lit and CCBC-Net, Ferguson, Baltimore, #MikeBrown, #TrayvonMartin, #EricGarner, #TamirRice, #BlackLivesMatter, and #SayHerName had sparked the national consciousness about race.

The center of gravity of children’s literature discussions had moved from Child_Lit and CCBC-Net to social media, much to the consternation of some. Conversations about racism and whiteness had often been contentious on the listserv. They were just as vinegary on Twitter, Facebook, and the blogs, only this time, anyone could chime in, not just the initiated…

One of the people who had always spoken up for social justice on the Child_Lit listserv was Debbie Reese. There were others, like the eminent author, storyteller, and educator Eleanora E. Tate. But whenever conversations turned racist, Debbie would speak out.

Debbie spoke up about the problems in A Fine Dessert. She used American Indians in Children’s Literature to support those who were advocating for the publisher, author, and illustrator to answer concerns. She tracked all the responses to the controversy. A few years later, she and I would co-author a ChLA honor award-winning article about #SlaveryWithASmile with K.T. Horning, the longtime director of the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin - Madison. I watched her speak up about Black critics’, parents’, and activists’ concerns about A Fine Dessert and A Birthday Cake for George Washington.

Debbie and I had started to develop a friendship outside of Child_Lit before then. My first few years on the tenure track were very difficult. She was one of those who supported me most when I experienced racism, sexism, classism, ableism, and elitism during my first few years at Penn.

During my worst moment last decade, when I thought I’d need to walk away from the professoriate, Debbie sat on a Skype call while I cried and cried and cried…

She was there for me in my worst moment.

I am unfailingly loyal to my friends.

Back then, I admired Debbie for her courage. She spoke up when few did back in the Child_Lit days. There were so few of us back then. Her courage in the face of discrimination cost her everything, even tenure, but there she was, years later, fighting on, supporting younger scholars in the field. Encouraging us whenever we faced microaggressions. Cheering for our victories.

She stood alone as a Native woman critic in a field that is as anti-Native as it is anti-Black. Being in the trenches in the days before we had much backup, I really admired that about her.

Some critiqued her style. But I was in awe. Coming up in the field, I valued her as someone who didn’t sell out, who encouraged me and other scholars in our generation to stand up straight and tall. Debbie was always loyal to her family and friends, her nation, all Indigenous peoples, and the work of diversifying and decolonizing children’s literature.

That’s how I saw her.

I don’t throw away my friends lightly.

If you are my friend, I am going to try to take your word at face value. I am going to defer to you if something’s your lane. I am going to trust you.

I am going to fight for you.

Because I expect you to fight for me, too.

*

The one thing that being Black in Detroit taught me?

A Black woman’s worth to the rest of the world is based upon our ability to ride or die…

“Without question.” —Okoye, #BlackPanther.

If we say “no,” or try to have any boundaries whatsoever? Any lines folks shouldn’t cross?

That’s often the end of the friendship.

A Black woman’s worth lies in our usefulness to people.

I’m gonna ride ‘til I can’t no more.

*

This blog post isn’t really about Debbie.

I know that some of you were expecting it to be, popcorn in hand.

Brawl between two #DiversityJedi! Black vs. Native! Drag her! Let’s go!

That’s what you wanted. Here, on my blog.

In a pandemic.

During a digital age Great Depression.

With the ashes of buildings still smoldering around the country.

With the blood of George, Breonna, Ahmaud, and so many others who were once Black children and teens crying out from the ground.

Please.

This blog post isn’t just about Debbie’s threads yesterday, now deleted.

This blog post isn’t just about my rift with Debbie, which is private, and not up for display.

This blog post is about antiblackness in children’s literature, and the unbearable burden that children’s literature places upon Black women.

It’s not just that one individual in children’s literature criticism is antiblack.

The whole damn field is antiblack.

This blog isn’t about just one person.

It’s about all of you.

All of us.

We have all been complicit.

(Me too.)

*

A year ago this month, a group of Black women pulled me aside at ChLA 2019 in Indianapolis.

“We need to talk,” they told me.

I was pretty ill during the conference last year. I’d been getting sick since early 2017, but as Black women do, as every single person, particle, and atom in this reality expects us to always do, I kept piling on things and putting my health on the back burner.

The urgency of my sisters’ concerns made me press pause and push those piles aside.

We went to a nearby restaurant.

“Ebony,” they said. “ChLA is antiblack. This so-called diversity ‘movement’ is antiblack. Your friends are antiblack. We are tired of it.”

And we had a long conversation about it. I said that I would address their concerns with the Kidlit Folks Who Were Not Black.

I had good intentions. I wanted to intervene. I wanted to fix it.

I called and texted and DMed folks while I was still in Indianapolis… mostly, it wasn’t received well. The concerns were viewed as hurt individuals, not systemic.

I put it on the back burner.

I continued my book tour, until I got very sick.

I was on medical leave in the fall. Partial bedrest, then surgery and recovery.

Spring semester began. I was teaching 3 courses, while cramming everything I had to make up into January and February.

Then the pandemic happened.

And here we are. Still in a pandemic. But so much more is going on, too…

Like I said, context is everything.

*

I love a good amen corner.

That’s why I’m here, writing this, instead of finalizing my book, 10 days after finishing my second rewrite.

Because I just love saying “amen” when I’m along for the ride.

I was born loving the call and response of a good conversation, being in agreement with people.

Going along to get along…

Since I was a toddler, I have been the easygoing, studious but friendly, “love all, serve all” Thomas girl. We are all fiery, though. (If you think I’m something, you should meet my sisters.)

Let me make something clear:

Behind the scenes, I have definitely been critical of some of the tactics of the recent social media diversity movement. My questions and critiques have mostly been private. (That’s Detroit, too - can’t ride if there’s no united front.)

But my dissent’s been out there, too.

On @Ebonyteach, I constantly raised questions about our movement’s focus on individuals and personalities instead of laser focus on systems and behind-the-scenes issues. Repeatedly.

I questioned dragging authors and illustrators instead of publishers. The #StepUpScholastic movement was excellent, because it accomplished just that.

I believe in accountability. I have been subjected to accountability.

(I’m a Black woman. You don’t let us get away with anything.)

Changing children’s literature should be about books and young people. Not about personality conflicts.

I have amplified controversial critiques of many books. Sometimes, I have agreed with them. Sometimes, I haven’t (ride til I can’t no more). Sometimes, I’m so damn busy that I can’t think straight. I’ll get a text or DM, go to Twitter, Tweet, RT, spin out a thread, and then back to #ProfessorLife…

I will admit that I do not tone police my friends. I have refused to do that.

I don’t check how my friends choose to fight, because I certainly can go to war, too… and I have… receipts are long and deep.

I wasn’t about to be that person who tone polices.

Instead, I gave my #DiversityJedi friends the very best that I could spare, given all that I’ve been juggling. More than I should have, without pushing back and asking questions.

I’ve re-assessed my initial generous readings of several books because I wasn’t going to be that person.

I’ve taken at least two major public social media hits in amplification and support of Native issues. The latter could have ended my career. I took it gladly, feeling that I was on the side of justice.

I prioritized #ownvoices criticism above all else, especially when it came to diverse books.

I prioritized #ownvoices criticism over my sisterhood with Black authors.

I prioritized what I sincerely believed was legit #ownvoices criticism of Rebecca’s books — I was told these things were sacred, and I’m not part of those cultures — until yesterday.

However, I can no longer be part of personal vendettas that are not about the text, the story, the book. In communities that aren’t mine…

…just because I’m loyal.

Black girls are raised to be loyal.

I’m a Black woman who’s committed to antiracist solidarity with Non-Black IPOC and White allies!

If I’m not loyal, what am I for?

We exist for others. Never for ourselves.

We help.

We serve.

Gratitude is expected. Endlessly.

We’re assumed to be ungrateful, even when we’re constantly helping.

It’s an entire problem.

Who is loyal to us?

Gonna ride ‘til I can’t no more.

*

Yesterday was not the first time I have been called in by other Black women in children’s literature about something a friend of mine has posted.

Until yesterday, I’ve mostly let things be.

I’ve tried to smooth things over with both sides.

That’s me. Smooth things over. Coalition building requires sacrifice. Eyes on the prize.

Yesterday was not like previous times. A lot is going on with my Black family and friends in this pandemic, Great Depression, racially violent, don’t-blame-White-people-for-our-fascist-President era.

A lot is going on at my institution, at all higher ed institutions, right now. I don’t talk about it much on social media. #ProfessorLife in a pandemic is complicated.

I don’t need sympathy.

I need space.

Let me be clear: This is not the first time I’ve learned that someone in children’s literature criticism did not reciprocate friendship and colleagueship.

Let me be even clearer: This is not the first time during this pandemic I’ve been let down by someone in children’s literature criticism that I thought of as a mentor, colleague, and friend.

In that case, a person I valued as a mentor, colleague, and friend didn’t see me. There was chastisement, immediate demands, and the implication that I’d attacked them — when they were on my Facebook page.

In this case, a person I valued as a mentor, colleague, and friend didn’t hear me. When I went public with my disagreement, it got characterized as a career move.

In both cases, I have been left brokenhearted.

You don’t see your Black colleagues.

You don’t hear your Black colleagues.

If you don’t, are we friends?

Were we ever friends?

Why do we use the word “friendship” to characterize these interactions?

I try to remember that I once loved this field, and that I tried my best to be good to the people in it.

This is not the first time I’ve been let down by children’s literature criticism.

I’m sure it won’t be the last.

*

Yesterday, I resigned as a board member of the Children’s Literature Association.

I sent a very professional letter. I’ve already heard from a few folks, who sent nice notes in response.

Last Friday, I began to realize my priorities weren’t in order. I need to do less, clear my plate, dig deeper, and most importantly, recommit to the family and communities who have sustained me.

I’m doing OK. I’m Black and woman in a pandemic, there’s too much on my plate, but all things considered, I’m mostly fine. Managing admirably, all things considered.

But I want to signal that children’s literature criticism has a problem. Once more, with feeling:

I am trying to signal that children’s literature criticism has a problem.

I do not need any more “Ebony, are you OK?” messages.

I’d like to leave you, dear readers, with a set of questions to think about.

*

1. “Black lives matter.” In what ways are Black people working in children’s literature criticism treated as if they don’t matter?

2. Black scholars in children’s literature criticism are sometimes expected to minimize and deprioritize Black concerns – to not be “too Black.” (I have certainly felt that pressure over the years.) How might we support Black scholars in the field across the career span as they work to center the needs and concerns of Black children, teens, families, and communities while engaging in “good” research and criticism?

3. The work of Black scholars in children’s literature criticism often gets compared unfavorably to White and NBIPOC critics doing the same work, weighed in the balance and found wanting. How can we bring children’s literature criticism into conversation with Black feminism, Africana studies, critical race theory, critical ethnic studies, and other fields where Black women’s methodologies for doing this work are valued?

In other words: What’s specifically Black about Black children’s literature studies?

4. When it comes to kidlit advocacy, everyone seems to expect Black scholars, critics, and advocates to crusade for everyone else’s causes. How can we bring conversations about reciprocity into the mix without engaging in unhelpful “Oppression Olympics” conversations? How can we be thoughtful about intersectionality without slamming Black folks' work for being insufficiently intersectional — especially when “intersectionality” is a term coined by a Black legal scholar to describe the position of Black women?

5. What happened to Black women in the field who disappeared before my time? A few of us are starting to excavate their work, but much more is needed. What happened to them? Were there Black women who were interested in children’s literature criticism, but were turned away? Can we engage in some kind of truth and reconciliation commission? I acknowledge the valiant efforts of sister-mentors like Michelle Martin and White allies like Kate Slater and Kate Capshaw to bring diversity into the mainstream of the field’s establishment, through organizations like ChLA, but much more is needed.

And the resistance to the field becoming more inclusive needs to stop.

6. Can we ever talk about the expectations from all the Nice People in Children’s Literature who have Done the Work and Constantly Need It to Be Acknowledged? Especially in a pandemic, but actually… always? Repeatedly?

Listen. I am grateful for those who have supported me over the years. However, now that I’m a mentor myself, I am skeptical of the “be ever grateful” stance that is required from younger scholars. I don’t require it, and frankly, witnessing me engaging in these gratitude rituals has harmed emerging Black scholars in our field.

I ask: What are the limits of these expectations of endless gratitude beyond collegiality and professionalism?

(This constant expectation of Black gratitude, and the implication that we are not, isn’t just in children’s literature. Black scholars are having many conversations about this dimension of our work right now. Expect follow-up, not just from me, but from Black folk all over. We are exhausted.)

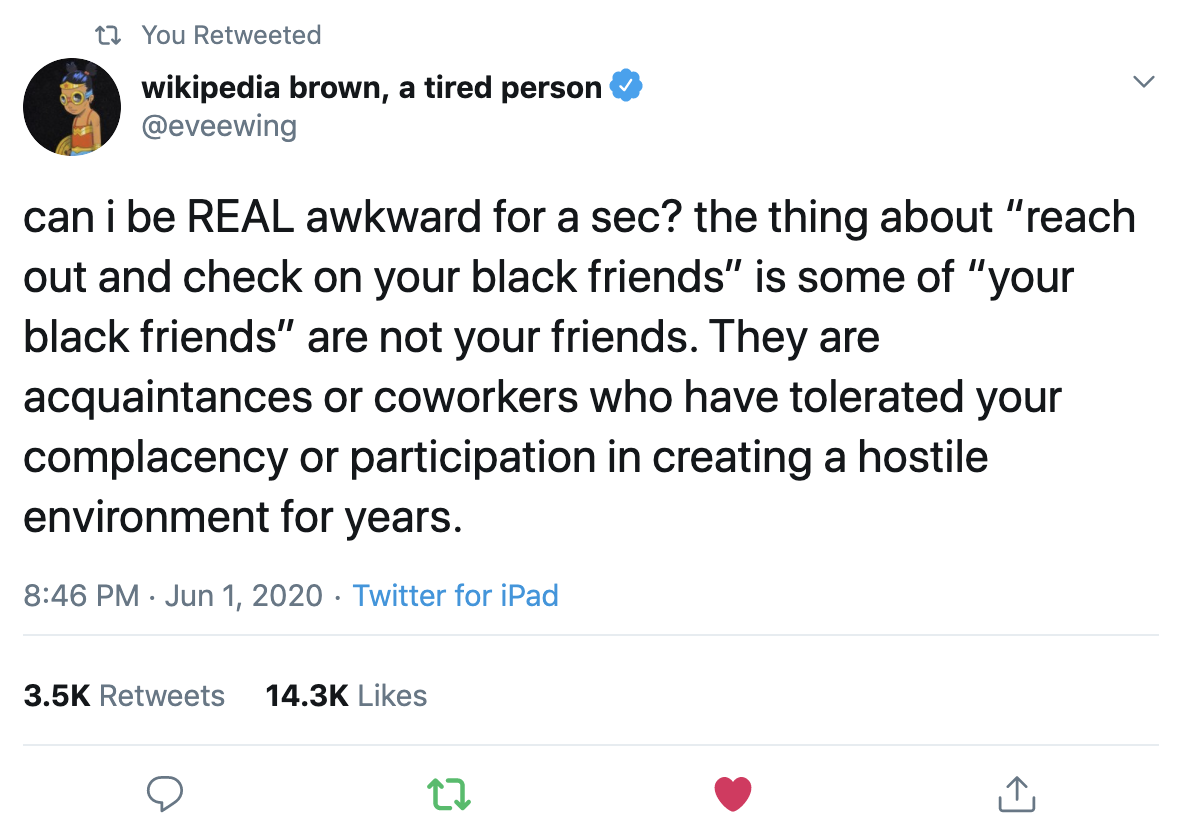

7. The re-centering of whiteness in antiracist children’s literature work is something that Black scholars have noted to me, privately. How can we avoid that? For instance, I enjoy and appreciate the Reading While White blog. I am glad for that work.

But I’ve noticed that some in the field routinely share posts from Reading While White, American Indians in Children’s Literature, Latinx in Kidlit… but don’t ever share posts from, say, the Brown Bookshelf, unless someone Black has died on camera.

Like now.

Black scholars, critics, and some authors have noticed people doing that – they’re seeing it and it feels awful. I have defended and explained this to other Black folks, saying that’s it’s important to share space, build coalitions, and “diversity isn’t just Black,” but I am tired of always explaining everybody’s good intentions.

8. I’m actually working (slowly) on an essay about this, but the way that Black scholarship in the field gets discredited because it doesn’t cover everything at once, or isn’t deemed good enough, is a problem. Some of this is legitimate — we need to sharpen our lenses, read more, and never stop fine tuning our work — but a lot of this sentiment is bogus.

I internalized quite a bit of this critique as a younger scholar because I trusted that kidlit scholars had my best interests at heart. I thought I needed to just measure up and do better.

However, new and emerging Black scholars are telling me some of the same things I heard 15 years ago: that US Black scholars are biased in critiques of non-US Black kidlit and education contexts, that we fail to consider that “diversity isn’t just Black,” and the like.

As a mentor myself, I have questions. I am thinking, and researching, and collecting data.

I wonder how these conversations might become more additive: “Have you also considered…?” “Perhaps a comparison can be made with…?” instead of always dismissing their Blackness. (Here, I have to shout out Michelle Martin and Kate Capshaw; that is the way they have patiently mentored me & others. They were and are patient with the process. They've helped me grow as a scholar, critic, and mentor.)

Mentoring requires faith that your mentee will get to the end of their journey. Instead of critiquing the limits of new Black scholars’ work, perhaps suggest more possibilities.

This is important. Black activist scholars and thinkers across fields are increasingly being dismissed as bigoted and/or inattentive to other forms of diversity. While it is the case that some of us are problematic, we all have a lot of learn, and all of us are imperfect, it’s curious that this generally comes up after we’re talking about race. White supremacy and antiblackness shape these negative interactions in ways that must be taken into account.

I am still thinking through a couple of additional factors, including the multitudes of scholars from all backgrounds who are never asked to consider diversity, let alone all of it, in their work, as well as those who are conducting scholarship on diversity in children’s literature simply to discredit it.

(I did not come to the conclusion that children’s literature is antiblack as hell lightly.)

9. Finally, is there any room in children’s literature criticism for Black scholars who make people who aren’t Black feel uncomfortable?

The work of Megan Boler and Michalinos Zembylas on the pedagogies of discomfort may be useful here:

Boler, M., & Zembylas, M. (2003). Discomforting truths: The emotional terrain of understanding difference. In P.P. Trifonas (Ed.), Pedagogies of difference (pp. 115-138). London: Routledge.

I’ve noticed that lately, I’m making folks less comfortable. I’m still the same person, just older, more weary, with much that keeps falling off my plate.

But honestly? I think that matters. I’m not the young ingenue any longer.

My experiences during the pandemic have left me wondering whether the people in our field actually want Black colleagues.

*

These are my questions during a pandemic, at a time of heightened racial tension and violence.

Scattered thoughts. Wonderings. The brain-children of weariness, of sighs, of starting to tense up whenever the notification bells ring with all this Concern.

Right now, I’m all talked out. What I’ve shared here is long, but it’s the tip of a very large iceberg.

Honestly? I am trying to figure out how to continue in this field and stay Black.

In a pandemic, with Black lives in the crucible, there has been little mercy, respite, or rest for Black people.

Black people are human. We have limits. We need things.

Right now, a lot of us just need space. We have a lot of processing that we are trying to do, while tending our sick, mourning our dead, trying to keep everyone sheltered, fed, and watered, and staying as balanced as we can...

“Are you OK, Ebony?” I keep hearing. (Those who ask this incessantly aren’t close enough to ask. I wish they’d stop. Those who are my nearest and dearest know.)

I’m OK. As OK as a Black woman in 2020 can be.

I’m OK. Our field is not.

Please stop emailing, texting, DMing, and calling me. I keep asking you not to do this, because yes, I am still comforting you.

You’re saying Black lives matter.

Don’t just talk about it.

Be about it.

It stops today. Individualization of this systemic problem stops today.

Me, Ebony, being the Black Friend you can point to in order to say you’re not antiblack stops today.

Are we friends?

No. We work in the same field, and we have been friendly, but friends don’t treat friends like this.

Children’s literature criticism is antiblack.

I apologize to Rebecca Roanhorse, Justina Ireland, and to other Black women authors who have been subjected to personal attacks from Debbie and others whom I considered friends.

Public personal attacks are not what professional critique is all about. They delegitimize critique. They detract from the substance of literary criticism.. I should have paid more attention to this, and done this call in, and subsequent call out, long before now.

I apologize to my fellow Black women children’s and young adult critics and scholars, whose concerns about rampant antiblack racism in our field I said I would take on, and should have prioritized. For your sake, I won’t name you — but you know who you are.

I love you. I see you. And I hear you. I’m not too busy for you.

I apologize to my fellow Black women children’s and young adult authors, as well as my sista-professor friends, who patiently called me in, time after time, saying “What’s up with your friend?”

Thank you for not giving up on me. Thank you for caring for me, and pointing out that I was not being treated well here, in this field that I love.

Thank you for lifting my head and asking gently, but firmly, that I demand respect from a field that I love…

…but just can’t quite seem to love Black critics back.

Until children’s literature critics admit that antiracist work begins in our own backyards, nothing will change.

Until Black lives matter in children’s literature criticism, all this rhetoric rings hollow.